The following is a piece of fiction. Maybe. It was written by my father a long time ago about a place that may or may not exist, and about people and events which may or may not have actually existed or occurred. Possibly. Who's to say? Certainly not me.

-paj

A Pig Too Big

By Rick Johnson

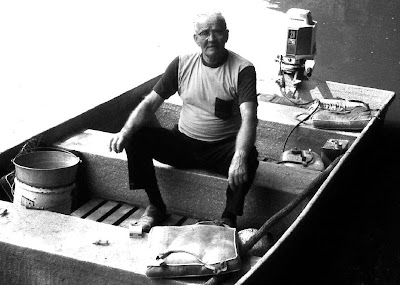

A stinging wind blew from the west up the river valley, tugging and shaking at the frost covered leaves. Light from the late autumn sun had failed, as yet, to give the morning much warmth. We paddled through the lace of mist rising from the river to the boat dock at the Stone Valley Boat Club, and tied up.

Although it was early, there was a great deal of activity at the club. Several cars were in the parking lot, and at least a dozen youngsters were scampering this way then that. Charlie and I got out of the boat and began the walk to the boat club to use the telephone. Charlie was very quiet during the walk. I was grumbling to myself at the interruption of our fishing, thanks to my error.

I thought how pleasantly the day had begun. We were off before first light. We intended to drift fish all day on the Stump Hole River, which meanders through the hills of south Stone Valley.

We paddled our way into the current and baited our hooks. We drifted about a mile, enjoying the pre-dawn stillness and solitude of the river. We had a couple of strikes, and I netted a nice channel cat.

We could hear the sounds of animals stirring in the brush and trees along the bank. The rumble of a B&O freight train, several miles away, was very clear, and occasionally we could hear roosters from the nearby farms announce the start of a new day.

Charlie spoke softly as he pulled in his line to check the bait, "Let's go over that spot again. I had a good hit."

I started the Evinrude, idled her down, snapped it in gear, and we began to move slowly up stream. We wanted to go about 30 yards upstream where Charlie got his strike, kill the motor, then drift back. We never got that far. The motor pitched out of the water, and I glanced back just in time to see the propeller fly off and plop into the water.

After I shut the motor off, I looked at Charlie in the pale half-light. He was grinning. I really hated that grin. I could see it and feel it. It said so much without a word being spoken. He lit a Lucky, and blew the smoke at me.

"Hit the rocks. Must'a been way out of the channel."

"Yep. A dumb trick," I said.

Good reasons and alibis were of no importance to Charlie. A person either knew a thing and could do it, or he couldn't. If he couldn't, he should say so, and not try to bluff it through.

Charlie's cabin was only a few hundred feet from my fishing shack, so I knew him well. I watched him silently, anticipating some acid comments.

"Should'a taken my boat. I should'a been operating," he muttered just loud enough to be understood.

It was a lesson. Had I been doubtful about my ability to safely navigate that early in the dim light, I should have said so. Charlie would not have been critical or thought less of me. Now, my ignorance had caused a problem which subtracted, at least in my mind, from enjoyment of the day.

The boat had turned sideways in the current, and we were drifting very slowly.

"Hell, I'm not going to let it ruin my day,” Charlie said softly. He cast out his line, then poured himself some coffee.

I lolled on the seat and transom of the boat, fishing, but not really enjoying myself. Gradually, dawn began to sift through the trees, and I could tell exactly where we were. Charlie, of course, knew all the while.

"Best I can figure, we'll drift by the Boat Club about nine or thereabouts," Charlie said as he gently cranked his bait. "We can get someone to take us to town to get a prop. Reckon you bent the prop shaft too?"

I knew Charlie's words were a request…"check us out…let's find out what's wrong."

I pulled the motor up and popped it into gear. By pulling the starting rope slowly, the propeller shaft rotated, and I could see if the shaft was bent.

"Looks like I buggered that up too," I said grudgingly.

I got that grin again.

"Well, hell, let's don't get bent up about it. I should have warned you. The water in this old gutter is low. You've probably never been through here in this kind of light when it's this low. That rock bottom back there had made a fool out of more than one man this time of year, including me. We'll get to the club and get 'er fixed and drink a little beer. Let's just fish an' drink coffee an' smoke an' enjoy ourselves,” he said as he cast his line.

His words made me feel a lot better. I concentrated on keeping the boat straight and let him fish. I figured I could learn a lot by watching him. And, if he talked, I knew I'd learn a lot more. But, he didn't talk. He fished and kept a Lucky dangling from his lips. By the time we drifted to the boat club, he'd added a nice size largemouth bass and two perch to the stringer.

Charlie broke the silence after he took a long look at the clubhouse far up the hill. "Jeeminnie, look at that hill. Noah'd been safe up there. What' say we wait around and try to get a ride up the back side?"

"If you want to stay here, it's okay. I'll go up and make a call or two for the parts and get some beer."

Charlie chuckled, "Like hell. Think I'm gonna' miss you ordering a prop and shaft an' not see all them guys grin an' give you the business. Why hell, I'd crawl up the hill."

I feigned a swing at him, and he laughed, "There ain't a one of 'em, if they'd admit it, ain't done worse. I'll guarantee it. An' if they ain't, they're going to."

Youngsters were somersaulting on the steep hill, and some others were sliding on a piece of cardboard on the frost-covered grass. As we started up the steps, the youngsters would flash by us going down hill, and then bolt past us as they ran back up the hill.

"It's a real easy thing to hate young people," Charlie said as he held tightly to the railing on the steps. "You see 'em taking these damned steps two, even three, at a time? An' most of 'em don't even use the steps, going up er' down. What a hellacious waste 'a energy."

We stopped every few steps so Charlie could catch his breath and cuss the kids. But one stop was mandatory.

More than halfway up the hill was a large oak tree, and hanging from one of its limbs was one of the biggest hogs either of us had seen. The huge white carcass was smeared with barnyard muck, and blood was running from a tiny hole between its eyes.

"Geez, what a hog. There's a river of lard an' two trucks 'a bacon in that baby," Charlie said in awe. "They must be fixin' to have a barbecue. He lit another Lucky and we continued up the hill, looking back a time or two at the hog.

Once inside the clubhouse, I went to the phone, and Charlie took a window seat so he could examine the hog. I soon located the parts for the boat and got a promise they would be delivered early that afternoon.

Everyone at the bar was grinning at me. Jerry was the first one to speak. "Lost a prop an' bent a shaft too, huh? You've been around too long to do that."

The remark prompted nods in unison from those at the bar. I looked at them, trying to conjure up a brilliant reply. All I could do was lie.

"Well, hell, guys. What could I do? Charlie latched into one so big it pulled us right into the rocks."

A chorus of "bullshits" rang from the bar patrons. I laughed, and carried a couple of beers to where Charlie was seated.

"You handled that real good," Charlie said with a smile. He then turned his attention to the hog. "Never in my life have I seen a hog that big used for a barbecue. It must weigh 600 pounds," he said with a disbelieving shake of his head.

We talked for a while about what a beautiful day it was, and finished our beer. Charlie ordered two more, and Johnnie, the bartender, brought them to us.

"Goin' to have a barbecue, a big one by the looks of that hog," Charlie said.

"Boy, are we," Johnnie answered with a vigorous nod. "Ain't that hog a beaut'?"

"Sure is," Charlie said. "Where you got the fire goin'? With a hog that size, you should've had a pit dug an' the fire started yesterday."

Johnnie gave Charlie a blank look. "I don't know nothing 'bout that. Bob, the commodore, is handlin' all that. We got more'n a hundred people comin' tonight." Johnnie walked back to the bar and we saw him talking to the commodore.

The commodore, resplendent in designer jeans, loafers, and fringed leather jacket, glanced our way. After a decent interval, he wandered in our direction. "Hi Charlie, Mac. That sure was a good one about the fish pulling you into the rocks," he laughed.

Charlie took a swig of beer and said, "He oughta' be good at something."

Turning to Charlie, commodore Bob said, "So you think we should have had a pit dug and a fire started yesterday." His voice was loaded with sarcasm.

"Oh, don't pay any mind to me. I just asked a question. Like the ones I'm fixin' to ask you now. Don't you think you should get at gutting that hog? It's hangin' there, and the day's gettin' warmer. The meat might taste funny if it ain't gutted soon. And, that animal ain't been bled."

Bob took a step back with a quizzical look, "Why we were just going to get to that." Bob turned and went to the bar, and soon, several men were gathered around him.

Charlie took a swig of beer and grinned at me. It was that grin he used when I'd fouled up.

"Okay. What did I do now?"

"Not a thing. I just got the notion that if we stay here, we're going to see the damndest sights we've ever seen."

"You mean the hog?"

"Yep. It'll be a hell of a show."

Bob and a platoon of men left the bar and trotted out the front door.

"Let's give 'em a little time, an' we'll go out and watch."

We finished our beer and walked out on the porch. The bright sun had taken the harsh chill from the air.

The men, with commodore Bob in command, were clustered around the hog. One man was high on a ladder with a knife in his hand. Two men, holding a wheel barrow, stood ready to catch the entrails.

The man with the knife made a deep, long gash in the hog's belly, and soon, with oozy thumps, the entrails fell into the bed of the wheelbarrow. It filled rapidly to overflowing, and the man on the ladder was not finished. The two men holding the wheelbarrow on the steep hill were having difficulty handling the incline and the rapidly increasing weight, and asked for help. Two more men rushed to their aid, and in doing so, hit the ladder, knocking it away from the tree and into the hog's carcass. The man on the ladder quickly clutched the tree and righted the ladder.

The hog's huge bulk was set in motion. The hog swung back and toppled the man and the ladder. He landed in the already overloaded wheelbarrow, and knocked all four men down. The wheelbarrow, with its unwilling passenger, slid down the hill, where it tipped over, spilling man and offal to the ground.

Even at my dumbest trick, I'd never seen such glee on Charlie's face. "That was a classic," he said as a laugh began to build. "I really don't want to do this," he managed to say. "I'm just having a coughing fit if they ask what's wrong." He then bent over and laughed, with coughs interspersed, for a long while. The commodore and his troupe were much too busy to pay any attention to us.

While we struggled to control ourselves, they tried to salvage the situation. They picked up the offal, put it in the wheelbarrow, and carted it to the river. They then returned up the hill where they finished the task of gutting the hog.

Charlie was a retired truck driver. He had worn out many trucks and his lungs during countless trips across the country puffing on Lucky Strikes. He was short on formal education, but experienced in what it takes to get along. He knew more about fishing the river than anyone I'd ever met. Everything he did he performed with deceptive ease. He amazed me with his knowledge of mechanics, electricity, and plumbing, as we worked out problems with my fishing shack. But he was often maddening. He'd watch me work, and let me make all sorts of mistakes, and then give me that grin. If I asked him a question, and he knew the answer, he'd patiently and completely tell me the answer. And, he was always right.

I was having just as big a laugh as Charlie at the commodore's crew and the hog, but I wondered why Charlie didn't speak up and give them some pointers.

"You've roasted hogs before, haven't you?" I asked.

"Yep. Hogs, pigs, 'n quite a few steers. It's a real art. These kids are going at it like it was a wiener roast."

"Why don't you talk to them, give 'em a point or two?"

He looked at me with disbelief. "You heard the commodore when I asked about the fire. Why, if I opened my mouth, him and his helpers would do their best to make the old man feel silly. Young'ns take to advice like they take to castor oil. Nope, I'm gonna' keep my oar out'a their pond, unless they ask. Besides, I go to talkin' too much an' we might miss the show. This could be better' n fishing."

I fetched two more beers and sat down beside Charlie. The commodore and his men had finished their clean-up, and left the hog swaying on the tree. They soon dashed up the steps and returned with several buckets of hot water. They doused the hog and then, with sharp knives, began to scrape the carcass from the rear hooves to the snout. The hog gleamed stark white in the warming sun.

That task finished, the commodore led his crew up the steps past us. He took the steps two at a time with a stride that made me wish he'd stumble. Most of the troupe imitated his gait and demeanor. But the man who rode the wheel barrow full of offal down the hill didn't have much starch in his gait. He was bringing up the rear, trudging slowly up the steps covered with mud, blood and manure. He looked at us and gave a rueful nod. "Got to get a bath an' clean clothes. I'm a mess."

For an instant I thought Charlie was going to hammer him verbally, but he smiled kindly and said, "Yep."

After the straggler went by, I noticed that Charlie was beaming again. "Notice anything?"

I looked at the hog. It looked clean…very clean. Ready to roast, I thought. "No. Guess I don't see anything unusual."

"Well, that hog's growing. Growin' faster than it ever did when it was alive. An' those boys a' got some more surprises comin'."

"You gonna' tell me or are you gonna' let me be surprised?"

"I'll just wait. It could be better than that hog swingin' and knockin' everything an' everyone ass over tea kettle."

"You still going to keep what you know to yourself?"

The exuberance vanished.

"There's two things in a young man that's always bigger 'n his body. That's his pride an' his ego. Wouldn't do to talk now. They know they've messed up, but they're gonna' thrash around and see it through. Least the commodore's goin' to. Couple of them other boys are ready to listen to someone. But…"

He drawled the word and bit of the 't', "they won't go against their leader."

He lit a fresh cigarette from the butt he was smoking, took a deep puff and exhaled. "The only way I'm gonna' leave here is in an ambulance, an' I'll a' died laughing."

"That mean no more fishing today?"

"I'm telling you, I'd give up fishin' permanent before I'd miss this hog roast. Hog wrestle, I mean."

I examined the gleaming white propeller and the shiny new propeller shaft. "You think this is gonna' be so good I might want to write about it?"

Cackling and slapping both his knees, he said, "Write about it? If you write about it, and what's comin', you better never come back here."

I waited for him to stop laughing, then said, "Okay, you wait here. I'll get the boat ready to go, whenever that might be, then come back up here."

He nodded agreement, then added, "Better clean those fish and put 'em in the cooler. We'd better have somethin' to show our wives when we get back."

I grinned at him, turned and started down the hill. About the time I got to the parking lot, I heard him say, "Get back here soon or you're gonna' miss something." I motioned that I'd heard him and headed for the boat.

I kept wondering why Charlie was getting such a kick out of the foul-ups we'd seen. Sure, those guys were in a mess, but it seemed sadistic for Charlie to let it continue.

As I walked, I decided not to argue the matter with him. He had a devastating way of always being right. I'd clean the fish and repair the motor, and hope that whatever it was that Charlie was sure would happen, would happen quickly so we could return to our fishing.

The sun was very warm, so I shed my jacket while I did the chores. After stowing the fish in the cooler, I decided to test the motor. I untied, fired the engine, and took a short hop. The Evinrude ran as good as new. I pulled back to the dock, tied off, and walked back toward the club. I walked past the hog, and was nearing the top of the hill where Charlie was seated on a step. Motioning with his empty bottle toward the hog, he said, "Take a look at that hippo. Notice anything?"

I looked back and carefully examined the bulging white carcass…sporting a dozen or more nicks from its haircut, but nothing more. "Looks like its been in a knife fight…all those nicks…but that's all I see."

"She ain't swinging no more. She's growed a foot or more. Them nicks you see is just a trifle now. Just wait."

I looked again. The hog had grown. The snout and head were laying on the ground, and the animal's shoulder was almost touching the ground. The whole carcass looked curiously elongated.

"You got to chill an animal out quick after a kill. You have to bleed 'em quick, and can't hang one up in weather this warm. It'll do all sorts'a tricks. Wait until they start tryin' to handle it. They'll think that hog's still alive. Oh hell, let's have another beer," Charlie said.

"I'll go get 'em. Sit still." As I headed to the club, I saw the commodore and his crew marching along the access path carrying a long metal pipe.

Charlie said, "If that pipe's the spit, they might as well have a coat hanger."

I hurried inside the club, got the beer, and returned.

The commodore had cut the rope holding the hog in the tree, and the crew had lowered the carcass to a section of canvas. With two men holding the long pipe in the hog's mouth, another man began trying to force the pipe through the animal's neck. After several pile driver-like thrusts, he succeeded. Soon one end of the pipe protruded from the bulbous rump. Then, two men, working inside the animal's body cavity, used heavy gauge wire to fasten the backbone to the piece of pipe. The hog was laying on its side for this process.

Charlie watched without expression or comment.

"Okay, men. Let's pick 'er up and get 'er around to the pit," the commodore said. A pair of men dutifully took positions at either end of the carcass, and hunkered down preparing for the lift.

"On three, men," commodore Bob barked.

"One. Two. Three."

The men rose together with the hog on the pipe, giving their burden a strong jerk, and cleared the ground. The pipe first sagged a bit in the middle, then bent in a V-shape. Then, the hog, having been moved from the horizontal plane to perpendicular, swung slightly, all 600 pounds of it. The sudden shift of weight caused all four men to lose their footing, and they fell, dropping the hog. The hog and bent pipe began a slow, herky-jerky roll down the hill. It stopped when the ends of the pipe gouged deeply into the ground, leaving the hog almost upright on its feet, with a long and severely arched back.

Charlie had changed color. He wasn't making a sound. He was convulsed and gasping for air. He turned dark red, then purple, and red again, before he made a sound. But what a sound. It was a howl punctuated with the braying of a jackass, deep coughs and wheezes, and the slaps of his hands on his thighs. When he was finally able to talk, he said, "Jeeze, Almighty damn, why don't we have a movin' pitcher cammer'?" He pulled his hanky from his pocket and wiped his eyes. Tears were streaming down his cheeks.

Commodore Bob turned toward us. The arrogance had been replaced with anger. He said, "Glad you're enjoying yourselves. Why don't you take Pops to the men's room. He's enjoyed himself a little too much." He jerked his head around to try to concentrate on the hog's predicament.

I looked at Charlie. He was laughing so hard he hadn't heard what the commodore said. I nudged Charlie several times until he quieted down enough to listen to me. "Let's go inside Charlie. You've wet your pants."

He looked at the wet stain on his trousers and burst out laughing again. As he roared, I saw the wet spot grow in size.

The commodore and his troupe were busy trying to rescue the hog and regain their dignity. While one group worked to remove the bent pipe, another began cleaning the hog again.

The commodore walked past us to the club. He was seething but silent.

When Charlie finally calmed down he said, "My rain pants are in the boat. Would you go get the old man's rubber pants so he can keep on pissin' and laughin'?"

"How could I refuse?" I went back to the boat and fetched Charlie's rubber drawers. When I returned, Charlie was in the clubhouse. He had taken a seat in the corner of the room. I gave him his pants and he went to the rest room, absorbing a barrage of remarks as he walked by the men at the bar.

When he returned, wearing the rain pants, he plopped into his chair. "I'm weak as hell from laughin'. I never been anywhere in my life where I lost my shorts and pants at one time. What a day."

He lit a cigarette and, blowing the smoke toward me, he said, "This is gettin' serious. Heard the boys at the bar say they sent out for some coke so's they can get a hot fire goin' in a hurry up in the barbecue pit. Some of the other boys have gone out for a stronger piece of pipe. They got a lot of company comin' tonight, and they don't wanna' look bad."

"I suppose you want to go up by the pit and watch?"

"I sure do. That old hog ain't through with these boys yet. An' if I had to make a bet right now on who's goin' to win, it'd be on the hog."

We walked out the back door and up the stone steps to the beer garden. We took seats as far out of the way as we could and still be able to see and hear everything.

An inferno was burning in a circular field-stone fireplace. Tall steel brackets were mounted inside the enclosure to hold the spit and hog when they arrived. Two men were heaving great chunks of wood into the blaze, and another was dropping pieces of coke into the center of the fire.

"They've got a fire hot enough to melt a boxcar, an' they're tryin' to get it hotter," Charlie said with a shake of his head. "Lord-a-Mighty, the devil don't have no fire that hot."

A while later, the commodore and his bedraggled band appeared on the rocky trail leading to the pit. The hog, now tied to what appeared to be a piece of heavy well pipe casing, had stopped its flopping around. It appeared to be well trussed to the piece of pipe. The men struggled up the steps with their burden, and began walking toward the fire. They quickly backed up, shying away from the intense heat.

"You've put too much wood on the fire," the commodore screamed. "Now, we've got to wait until it burns down. Someone go get that tarp out front. We'll put the pig on that."

"Can you hold 'er men until we get the tarp? Otherwise, we’ll have to clean the thing again," commodore Bob said. The sweating men nodded yes, and stood like good soldiers bearing the heat and the weight of the hog. In moments, a young man appeared with the tarp, spread it on the ground, and the men settled their load to the canvas.

"I'll buy everyone a beer," the commodore said jauntily.

All the men went inside, leaving us with the hog and the fire. The fire was like a blast furnace. It was getting so hot that the spit supports were glowing red. We were more than 20 feet away from the blaze, and we were sweating. The pig was less than 10 feet from the fire, and it was sweating too...not sweat...but lard. Fat had begun to ooze from the multiple knife nicks on the carcass.

We watched the hog and fire for a while, then I said, "If we don't leave soon, we'll have to go up river in the dark."

"Leave? Leave?" Charlie said in disbelief. "I'm gonna' see this through. I'll get us home. Quit worryin'."

I knew better than to argue. Besides, I was intrigued. I couldn't figure how they were going to turn that huge animal on the spit. I saw no crank for the piece of pipe, or any other mechanical apparatus to perform the task of rotating the animal.

One by one, the commodore's band reassembled. They were pretty well beer'd up by the time they returned. All of them had a beer in hand, and were laughing and joking. The commodore was a bit tipsy too. He was walking like a man on a rolling deck, but he wasn't going to leave anyone in doubt about who was in charge.

"Okay. Okay. We got to get things going here. The fire's about right. Might be a little hot, but that'll sear the hog and keep the juices in. By the time we rig up the pulley on the spit and put her on the posts, the fire will be just right."

Some of the crew went into the woods and began dragging back additional firewood. Another group settled down around one end of the spit. Into the hollow pipe they fit the collar of a pulley, and slipped a large bolt through pre-drilled holes to prevent the pulley from slipping. Another man came up the trail carrying a large electric motor he had mounted to a heavy plank. He had a large extension cord around his neck, and a sturdy looking power transmission belt.

Charlie looked at the men and the rigging and shook his head with wonderment. "I was puzzled about what they were gonna' do for power to turn that hog. The fat's in the fire."

Soon the motor was put in place outside the pit, near one of the spit supports, and the extension cord payed out to a power source. The crew of four men, two on either end of the pipe, settled the hog and pipe in the end bearings. The transmission belt was fit over the pulley on the spit, and the pulley on the motor.

Then, everyone moved back in order to watch the culmination of their efforts. Tiny drops of fat fell from the hog into the fire, flared up, then died out. On the commodore's command, the extension cord was plugged in. The torque of the big motor jerked the hog around in one, uneven revolution. The hog's motion stopped with it's back directly over the fire.

The V-belt began to slip, squeal, and smoke. There wasn't enough tension on the belt or enough power to rotate the bulk of the hog again. Meanwhile, what had been a trickle of fat running from the knife cuts had grown to a river, and flames grew higher and higher and did not burnout.

The V-belt caught fire. The electric motor began to belch blue-black smoke. Then, it arced with a flash of sparks and flames and blew up.

While the commodore and his crew were talking frantically, the hog continued to gush lard into the fire. The men were scurrying this way, then that. The fire very soon was so hot, none of them could get close. The pig was ablaze from snout to tail in a wall of flame. One man tried to beat out the flames, but the pole he used broke, and the broken pieces fed the fire a little more.

Then, one of the commodore's men emerged from the back door of the club with a fire extinguisher. Another man made his way toward the fire, pulling a garden hose which was spouting a small stream of water.

The commodore grabbed the man with the fire extinguisher. "You can's use that," he yelled. "It'll ruin the meat. Use the garden hose."

Water from the hose merely moved the spitting, cracking, flaming lard around, and failed to extinguish it. Motioning to the man with the fire extinguisher, the commodore and his cohort edged toward the holocaust. A cloud of white powder exploded toward the fire, and soon covered the barbecue pit and the blazing hog. The fire was knocked down in just a few seconds. A deep silence then fell on the area.

I looked at Charlie. He was wearing a somber expression. He refused to look at me.

The commodore was fidgeting. He had his thumbs hooked in his front pockets and was motioning with both hands, taking a few steps backward, then a few forward. "Can't we do something?" he bleated.

The men huddled around him. We saw a series of nods, and one man left the group. He returned with a huge pipe wrench on his shoulder. "Looka' here. This'll turn 'er," he proclaimed. He put the wrench on the pipe and managed to turn the hog three full revolutions. Then, the pipe snapped and the end supports, which had been heated cherry red, bent like pieces of licorice, and deposited the hog into the pit. The fire flared up again.

"Get the fire out. Get the hog out. Get the hog out of there, I mean, oh shit. Get it out. Damn. Damn. Damn." the commodore screamed.

A few more blasts from the fire extinguisher knocked the fire down again. Then, everyone drew close for a look. The hog was covered with a blackened paste of fire extinguisher powder, ashes, and burnt lard.

Charlie remained silent, although he did cast a few glances in my direction, which indicated he could not believe what he was seeing.

When the pipe was cool enough to handle, four men hoisted the pig from the pit and placed it on the canvas. "Let's scrub her up and build another fire," commodore Bob shouted. Part of the crew took buckets of water and rags and began to swab the hog once more. Another group cleaned out the pit and began to build another fire. This time, they used several bags of charcoal.

"We'll put the grill screen over the fire an' cut that baby up an' cook 'er in chunks, since we can't get the spit to work," commodore Bob announced.

Instantly, every man in the group produced a knife, and another assault on the porker began. After some effort, the huge head was hacked off and placed on a barrel. In a short time, the hog's thick hide and sinews had dulled all the knives.

Work stopped and another huddle took place. We saw another series of nods, and a young man left the group and went around the corner of the club. Every one got a fresh beer, and a few of the gang took long drinks from a bottle of whiskey. Soon, the young man returned beaming with pride. "I just got this today and I'm dyin' to try the little baby out. What could be better'n this?" He held up a brand new chainsaw for everyone to see. Some looked at him like a savior, but by now a core of skeptics had formed.

The chain saw snarled to life with a couple of tugs. Its handler stood next to the commodore for a few seconds, listening to instructions. Then, he walked over to the hog, which was being propped up by several of the men. The hog, now a sedate shade of gray with patches of black, was readied for its final torment.

As the youngster made his first cut, the tip of the saw threw a white stream of lard. As he continued cutting, that stream became darker and darker.

Over the sound of the saw, we could hear the commodore shouting, "Stop! Dammit! Stop!"

Puzzled, the young man killed the motor.

"Oh hell," the commodore cried. "That meat is ruined. We didn't know the saw had an automatic chain oiler. The meat is saturated with motor oil."

We decided to leave silently and unobtrusively. Charlie took the helm for the return trip. He navigated in the dark for the last three miles. When we tied up, he lit a cigarette and said, "Well, from what we've seen today, you'll always know why there'll never be a Navy Admiral come out of the Stone Valley Boat Club."

I laughed, then said, "Say, as we left the place did you happen to notice that old hog's head on the barrel?"

"Sure did. It was smiling wasn't it?"